Portulaca oleracea (

common purslane, also known as

verdolaga,

pigweed,

little hogweed, or

pursley, and

moss rose) is an

annual succulent in the family

Portulacaceae, which may reach 40 cm in height.

Greek salad with Purslane

Approximately forty varieties currently are cultivated.

[1] It has an extensive Old World distribution extending from

North Africa through the

Middle East and the

Indian Subcontinentto

Malesia and

Australasia. The species status in the New World is uncertain: in general, it is considered an exotic weed, however, there is evidence that the species was in

Crawford Lake deposits (

Ontario) in 1430-89 AD, suggesting that it reached North America in the

pre-Columbian era.

[2] It is naturalised elsewhere and in some regions is considered an invasive

weed. It has smooth, reddish, mostly prostrate stems and alternate

leaves clustered at stem joints and ends. The yellow

flowers have five regular parts and are up to 6 mm wide. Depending upon rainfall, the flowers appear at anytime during the year. The flowers open singly at the center of the

leaf cluster for only a few hours on sunny mornings. Seeds are formed in a tiny pod, which opens when the seeds are mature. Purslane has a

taproot with fibrous secondary roots and is able to tolerate poor, compacted

soils and drought.

A Purslane cultivar grown as a vegetable

Although purslane is considered a

weed in the

United States, it may be eaten as a

leaf vegetable. It has a slightly sour and salty taste and is eaten throughout much of

Europe,

the middle east,

Asia, and

Mexico.

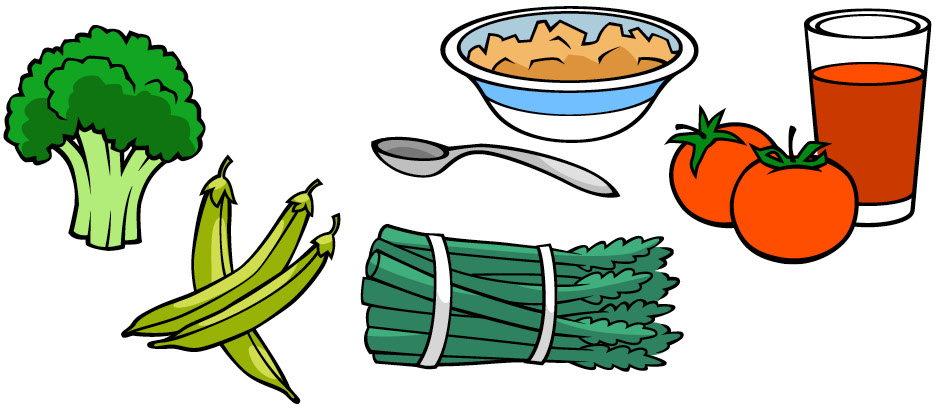

[1][3] The stems, leaves and flower buds are all edible. Purslane may be used fresh as a

salad,

stir-fried, or cooked as

spinach is, and because of its

mucilaginous quality it also is suitable for

soups and

stews.

Australian Aborigines use the seeds to make

seedcakes.

Greeks, who call it andrakla (αντράκλα) or glystrida (γλυστρίδα), fry the leaves and the stems with

feta cheese,

tomato,

onion,

garlic,

oregano, and

olive oil, add it in salads, boil it or add to casseroled chicken. In Turkey, besides being used in salads and in baked pastries, it is cooked as a vegetable similar to spinach. In

Albania it is called

burdullak, and also is used as a vegetable similar to spinach, mostly simmered and served in olive oil dressing, or mixed with other ingredients as a filling for dough layers of

byrek. In the south of Portugal (Alentejo), “baldroegas” are used as a soup ingredient.

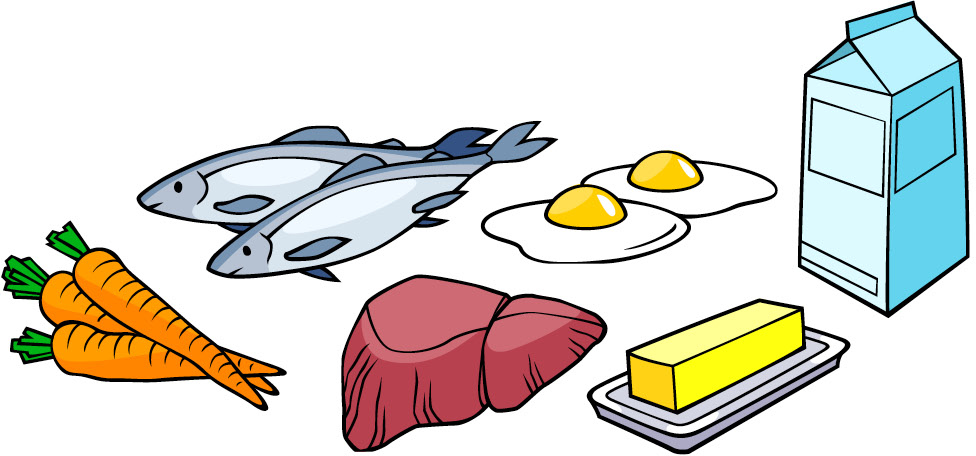

Purslane contains more

omega-3 fatty acids (

alpha-linolenic acid in particular

[4]) than any other leafy

vegetable plant. Studies have found that Purslane has 0.01 mg/g of

eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). This is an extraordinary amount of EPA for a land-based vegetable source. EPA is an Omega-3 fatty acid found mostly in fish, some algae, and flax seeds.

[5] It also contains

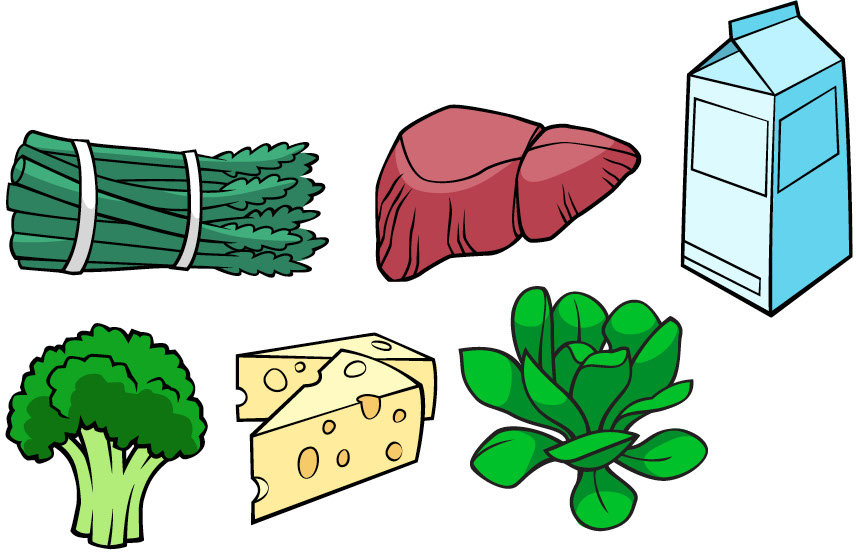

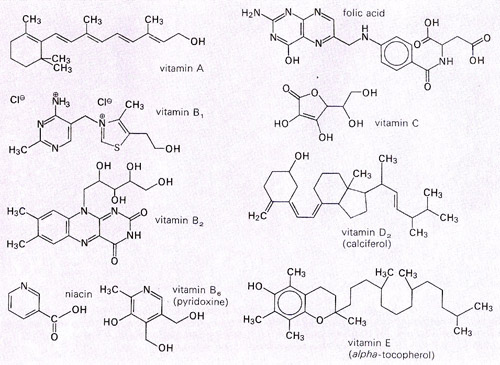

vitamins (mainly

vitamin A,

vitamin C,

Vitamin E (alpha-tocopherol)

[6] and some

vitamin B and

carotenoids), as well as

dietary minerals, such as

magnesium,

calcium,

potassium, and

iron. Also present are two types of

betalain alkaloid pigments, the reddish betacyanins (visible in the coloration of the stems) and the yellow betaxanthins (noticeable in the flowers and in the slight yellowish cast of the leaves). Both of these pigment types are potent antioxidants and have been found to have antimutagenic properties in laboratory studies.

[7]

100 Grams of fresh purslane leaves (about 1 cup) contain 300 to 400 mg of

alpha-linolenic acid.

[8] One cup of cooked leaves contains 90 mg of calcium, 561 mg of potassium, and more than 2,000 IUs of vitamin A. A half-cup of purslane leaves contains as much as 910 mg of

oxalate, a compound implicated in the formation of

kidney stones; however, many common vegetables, such as

spinach, also can contain high concentrations of oxalates. Cooking purslane reduces overall soluble oxalate content by 27%, which is important considering its suggested nutritional benefits of being part of a healthy diet.

[9]

When stressed by low availability of water, purslane, which has evolved in hot and dry environments, switches to photosynthesis using

Crassulacean acid metabolism (the CAM pathway): At night its leaves trap carbon dioxide, which is converted into malic acid (the souring principle of apples), and, in the day, the malic acid is converted into glucose. When harvested in the early morning, the leaves have ten times the malic acid content as when harvested in the late afternoon, and thus have a significantly more tangy taste.

Portulaca oleracea showing blooms

Seed pods, closed and open, revealing the seeds

Known as Ma Chi Xian (pinyin: translates as “horse tooth amaranth”) in

traditional Chinese medicine, its active constituents include:

noradrenaline, calcium salts,

dopamine,

DOPA,

malic acid,

citric acid,

glutamic acid,

asparagic acid,

nicotinic acid,

alanine,

glucose,

fructose, and

sucrose.

[10] Betacyanins isolated from

Portulaca oleracea improved cognition deficits in aged mice.

[11] A rare subclass of Homoisoflavonoids, from the plant, showed in vitro cytotoxic activities towards four human cancer cell lines.

[12]Use is contraindicated during pregnancy and for those with cold and weak digestion.

[10]Purslane is a clinically effective treatment for

oral lichen planus,

[13] and its leaves are used to treat insect or snake bites on the skin,

[14] boils, sores, pain from bee stings,

bacillary dysentery,

diarrhea,

hemorrhoids, postpartum bleeding, and intestinal bleeding.

[10]

Portulaca oleracea efficiently removes

bisphenol A, an endocrine-disrupting chemical, from a hydroponic solution. How this happens is unclear.

[15]

Purslane, also known as Khulpha, Khursa in Hindi or Ghol in Marathi, is a water-retaining plant that can reach a height of 6″ – 12”. It’s smooth, reddish, thick leaves are wedge shaped. The leaves are alternately clustered at stem joints and are greenish on top and purplish on the underside.

The very tiny yellow flowers are around 6 mm wide and depending upon rainfall, the flowers appear at anytime during the year. Purslane has a taproot with fibrous secondary roots and is able to tolerate poor, compacted soils and drought.

It’s smooth, reddish, thick leaves are wedge shaped. The leaves are alternately clustered at stem joints and are greenish on top and purplish on the underside.

All that purslane needs to grow is part to full sun and clear ground. They are not picky about soil type or nutrition. If you decide to plant purslane seeds, simply scatter the seeds over the area that you plan on growing the purslane. Do not cover the seeds with soil. Purslane seeds need light to germinate, so they must stay on the surface of the soil. If you are using Purslane cuttings, lay them on the ground where you plan on growing purslane. Water the stems and they should take root in the soil in a few days.

About a month after the seeds are planted, the first flowers will begin to appear. Once the flowers open, the seeds will begin to set within about a week to ten days. Since the Purslane is an invasive plant, it is difficult to get rid of. This is because the plant has stored enough energy for the seeds to continue to mature even after you pull the plant. Therefore, if you are trying to get rid of purslane, don’t try to compost it. If the compost pile is not hot enough to destroy the seeds, you will end up with more plants you don’t want.

Purslane is ready to harvest in about 2 months from the time the seeds are sown. Make sure to harvest it regularly and be aware that it can become invasive. Harvesting before it develops flowers will help cut down on its spreading. Generally, you can harvest two or three times before the plants are exhausted.

The erect, tangy and succulent stems are high in Vitamin C. The leaves contain the highest concentration of Omega-3 fatty acids found in land plants. This is 5 times more than Spinach and 10 times more than any Lettuce or Mustard. It also contains Vitamin A, Vitamin C, and some Vitamin B and carotenoids as well as dietary minerals such as Magnesium, Calcium, Potassium and Iron.

100 Grams of fresh purslane leaves contain 300 to 400 mg of essential fatty acids (EFAs). One cup of cooked leaves contains 90 mg of Calcium, 561 mg of Potassium, and more than 2,000 IUs of Vitamin A.

As a companion plant, Purslane provides ground cover to create a humid microclimate for nearby plants, stabilizing ground moisture. Its deep roots bring up moisture and nutrients that those plants can use, and some, including corn, will “follow” purslane roots down through harder soil that they cannot penetrate on their own.

As a

companion plant, Purslane provides ground cover to create a humid microclimate for nearby plants, stabilizing ground moisture. Its deep roots bring up moisture and nutrients that those plants can use, and some, including corn, will “follow” purslane roots down through harder soil that they cannot penetrate on their own (

ecological facilitation). It is known as a

beneficial weed in places that do not already grow it as a crop in its own right.

Widely used in East Mediterranean countries, archaeobotanical finds are common at many

prehistoric sites. In

historic contexts, seeds have been retrieved from a

protogeometric layer in

Kastanas, as well as from the

Samian Heraion dating to seventh century B.C. In the fourth century B.C.,

Theophrastus names purslane,

andrákhne (ἀνδράχνη), as one of the several summer pot herbs that must be sown in April (

H.P 7.12).

[16] As

portulaca it figures in the long list of comestibles enjoyed by the Milanese given by

Bonvesin de la Riva in his “Marvels of Milan” (1288).

[17]

In antiquity, its healing properties were thought so reliable that

Pliny advised wearing the plant as an amulet to expel all evil (

Natural History 20.120).

[16]

A common plant in parts of India, purslane is known as Sanhti, Punarva, or Kulfa.

- Marlena Spieler (July 5, 2006). “Something Tasty? Just Look Down”. The New York Times.

- Byrne, R. and McAndrews, J. H. (1975). “Pre-Columbian puslane (Portulaca oleracea L.) in the New World”. Nature 253(5494): 726–727. doi:10.1038/253726a0.

- Pests in Landscapes and Gardens: Common Purslane. Pest Notes University of California Agriculture and Natural Resources Publication 7461. October 2003

- Jump up^ David Beaulieu. “Edible Landscaping With Purslane”. About.com.

- ARTEMIS P SIMOPOULOS Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Antioxidants in Edible Wild Plants. 2004. Biol Res 37: 263-277, 2004

- Simopoulos AP, Norman HA, Gillaspy JE, Duke JA. Common purslane: a source of omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants. J Am Coll Nutr. 1992;11(4):374-82.

- Evaluation of the Antimutagenic Activity of Different Vegetable Extracts Using an In Vitro Screening Test

- A. P. Simopoulos, H. A. Norman, J. E. Gillaspy, and J. A. Duke. Common purslane: a source of omega-3 fatty acids and antioxidants. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, Vol 11, Issue 4 374-382, Copyright © 1992

- http://world-food.net/oxalate-content-of-raw-and-cooked-purslane/

- Tierra, C.A., N.D., Michael (1988). Planetary Herbology. Lotus Press. p. 199.

- Wang CQ. Yang GQ., “Betacyanins from Portulaca oleracea L. ameliorate cognition deficits and attenuate oxidative damage induced by D-galactose in the brains of senescent mice.,Phytomedicine. 17(7):527-32, 2010 Jun.

- Yan J, Sun LR, Zhou ZY, Chen YC, Zhang WM, Dai HF, Tan JW “Homoisoflavonoids from the medicinal plant Portulaca oleracea.” Phytochemistry. 2012 Aug;80:37-41

- Agha-Hosseini F, Borhan-Mojabi K, Monsef-Esfahani HR, Mirzaii-Dizgah I, Etemad-Moghadam S, Karagah A (Feb 2010). “Efficacy of purslane in the treatment of oral lichen planus”.Phytother Res. 24 (2): 240–4. doi:10.1002/ptr.2919.PMID 19585472.

- Bensky, Dan, et al. Chinese Herbal Medicine, Materia Medica. China: Eastland Press Inc., 2004.

- Watanabe I. Harada K. Matsui T. Miyasaka H. Okuhata H. Tanaka S. Nakayama H. Kato K. Bamba T. Hirata K.”Characterization of bisphenol A metabolites produced by Portulaca oleracea cv. by liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry.” , Biotechnology & Biochemistry. 76(5):1015-7, 2012.

- Megaloudi Fragiska (2005). “Wild and Cultivated Vegetables, Herbs and Spices in Greek Antiquity”.Environmental Archaeology 10 (1): 73–82.Noted by John Dickie, Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food (New York, 2008), p. 37.

- Noted by John Dickie, Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food (New York, 2008), p. 37.

more info………..

The stems and flower buds are also edible. Trim the tough stems near roots using a sharp knife. Cook under low temperature for a shorter period in order to preserve the majority of nutrients. Although antioxidant properties are significantly decreased on frying and boiling, its minerals, carotenes and flavonoids may remain intact with steam cooking.

In fact, among the many names given to purslane around the world, there are some like the old Arabic baqla hamqa or the Spanish verdilacas or yerba orate that mean crazy plant. It is a reference not just to its appearance, but to the madly unrestrained way it grows, spreading rapidly in all directions at ground level in a mesh of stems, roots and leaves, which is one reason why for many gardeners purslane is one of the most annoying weeds.

Added to this is its remarkable resilience — it stores water it in its succulent stems and leaves, allowing it to tolerate hot, dry conditions, and can produce over 240,000 tiny seeds per plant, making it really hard to remove. It’s no surprise that purslane has spread remarkably widely, growing in different forms in most parts of the world and known by a wide variety of names such as portulaca or little door, from the way its seed pod opens, or the Hebrew regelah or foot, since that’s near where it grows, though the most unusual must be the term from Malawi that translates as ‘the buttocks of the chief’s wife”, an apparent reference to the fleshy rounded leaves of some forms.

Despite this wide range, most botanical studies give India as the origin for purslane, and some writers, like the American expert on wild food, Euell Gibbons, have even labelled it “India’s gift to the world.” But it is a gift that we have largely forgotten about, since few people here eat purslane these days, or even know that this weed is edible. It is rarely cultivated, but gathered from the wild and only rarely appears in places like Bhaji Gully because few know its value, other than old people or poor migrants from rural areas who have some memory of eating it.

One who did know the value of luni was Mahatma Gandhi, and while it’s a bit of a stretch to describe purslane as his favourite food, as some of its enthusiasts abroad have done, he did recommend it to several people and, in an article in his magazine Harijan, he wrote about “the nourishing properties of the innumerable leaves that are to be found hidden among the grasses that grow wild in India.” He had discovered these while living in Wardha and following a diet of uncooked food that required what he felt was an unreasonable amount of purchases from the local market. So he was delighted when an ashram resident “brought to me a leaf that was growing wild among the Ashram grasses. It was luni. I tried it, and it agreed with me.” It soon was a regular part of his diet.

Gandhi’s recommendations, of course, are no guide to taste, since he didn’t believe in enjoying food for its own sake. But luni has a pleasant lightly acid taste when raw, though with a slightly grassy, earthy undertone that does take some getting used to. It is probably never going to be one of those foods you have to try-before-you-die, but it is not bad at all to eat, either raw in a salad, or cooked. I find that the version we get here, which is rather less fleshy than purslane I’ve seen abroad, is worth stir-frying or adding to a dal, which brings out a nice, slightly peanutty taste. Another interesting way to cook it is in the Persian style, first sautéing it with onions and then cooking with eggs to make a firm omelette that has a nicely herbal taste when cut up and eaten cold.

The real reason for valuing purslane though is not taste, but health. It has always had a reputation for medicinal properties, with physicians over the centuries, from India to the Middle East to Europe, recommending it for everything from reducing fever, removing worms and soothing urinary infections. But modern science has made clear why it is of such value: apart from providing significant amounts of vitamins A, B and C. and decent amounts of protein, purslane probably contains more omega-3 fatty acids than any other commonly available vegetable source.

These fatty acids are essential for reducing cholesterol and heart diseases, but their most easily accessible source is oily fish, which makes it hard for vegetarians to get them. Some health conscious ones do force themselves to swallow fish oil capsules, or eat alsi (flax seeds) which are also a decent source of omega-3 acids. But purslane is probably a better source, and can be cooked and eaten as part of one’s meal. (The only caution is for people prone to kidney stones, since it also contains high levels of the oxalates which cause them). Luni may seem like a crazy thing to eat, but when people around the world are realising the value of this Indian plant, it is the way we are letting it become forgotten that may be what is really loony.