Licorice Inhibits 92% of Breast Cancer Cells & Slows Growth by 83% in Vivo:

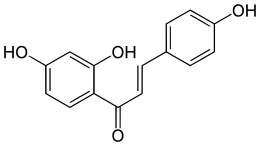

Isoliquiritigenin

Isoliquiritigenin

Isoliquiritigenin, a natural licorice compound, inhibited 92% of human breast cancer cells (both ER+ and triple-negative) in vitro after 48 hours of treatment in this new study. When given to mice, it resulted in breast tumors 83% smaller than untreated mice after 25 days.

Researchers discovered this licorice compound was not only cytotoxic to the breast cancer cells but also profoundly reduced the key angiogenesis factor VEGF by up to 85%, thus disabling the cancer from connecting new blood supplies to feed the tumors. Licorice is a powerful herb which has already shown strong activity against prostate cancer, colon cancer, cervical cancer, leukemia and others in lab studies.

Although used as a candy in the West, licorice root has been used as a medicinal herb for centuries in traditional Chinese and Ayurvedic medicine for treating asthma, allergies, stomach ache, insomnia, inflammation, viral infection and many other conditions. Licorice is also a proven adrenal booster, which makes it a great alternative to caffeine in fighting fatigue and boosting energy levels.

Bottom line: this super-herb could be a great addition to a healthy diet centered on organic vegetables, fruit and whole foods. And if you want to limit your sugar intake, it’s simple to make as a tea. read all this at

Liquorice or licorice (/ˈlɪk(ə)rɪʃ/ lik-(ə-)rish or /ˈlɪk(ə)rɪs/ lik-(ə-)ris)[2] is the root of Glycyrrhiza glabra from which a somewhat sweet flavor can be extracted. The liquorice plant is a legume that is native to southern Europe and parts of Asia. It is not botanically related to anise, star anise, or fennel, which are sources of similar flavouring compounds. The word 'liquorice'/'licorice' is derived (via the Old French licoresse), from the Greek γλυκύρριζα (glukurrhiza), meaning "sweet root",[3] from γλυκύς (glukus), "sweet"[4] + ῥίζα (rhiza), "root",[5][6] the name provided by Dioscorides.[7]

The isoflavene glabrene and the isoflavane glabridin, found in the roots of liquorice, are xenoestrogens.[10][11]

A, phase I metabolites of ILG formed during incubation with rat liver microsomes and NADPH. Based on accurate mass measurements, HPLC retention times, MS/MS analyses, and comparison with data reported by Guo et al. (18), the structures of metabolites M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7 were assigned as liquiritigenin, 7,8,4′-trihydroxychalcone, sulfuretin, 7,3′,4′-trihydroxychalcone, davidigenin, trans-6,4′-dihydroxyaurone, and cis-6,4′-dihydroxyaurone, respectively. B, structures of ILG glucuronide conjugates formed by rat liver microsomes in the presence of UDPGA.

The world's leading manufacturer of liquorice products is M&F Worldwide, which manufactures more than 70% of the worldwide liquorice flavors sold to end-users.[13]

Liquorice provides tobacco products with a natural sweetness and a distinctive flavor that blends readily with the natural and imitation flavoring components employed in the tobacco industry, represses harshness, and is not detectable as liquorice by the consumer.[16] Tobacco flavorings such as liquorice also make it easier to inhale the smoke by creating bronchodilators, which open up the lungs.[17] Chewing tobacco requires substantially higher levels of liquorice extract as emphasis on the sweet flavor appears highly desirable.[16]

In the Netherlands, where liquorice candy ("drop") is one of the most popular forms of sweet, only a few of the many forms that are sold contain aniseed, although mixing it with mint, menthol or with laurel is quite popular. Mixing it with ammonium chloride ('salmiak') is also popular. The most popular liquorice, known in the Netherlands as zoute drop (salty liquorice) actually contains very little salt, i.e. sodium;[18] the salty taste is probably due to ammonium chloride, and the blood pressure raising effect is due to glycyrrhizin, see below. Strong, salty candies are popular in Scandinavia.

Pontefract in Yorkshire was the first place where liquorice mixed with sugar began to be used as a sweet in the same way it is in the modern day.[19] Pontefract cakes were originally made there. In County Durham, Yorkshire and Lancashire it is colloquially known as Spanish, supposedly because Spanish monks grew liquorice root at Rievaulx Abbey near Thirsk.[20]

Liquorice is popular in Italy (particularly in the South) and Spain in its natural form. The root of the plant is simply dug up, washed and chewed as a mouth freshener. Throughout Italy unsweetened liquorice is consumed in the form of small black pieces made only from 100% pure liquorice extract; the taste is bitter and intense. In Calabria a popular liqueur is made from pure liquorice extract. Liquorice is also very popular in Syria where it is sold as a drink. Dried liquorice root can be chewed as a sweet. Black liquorice contains approximately 100 calories per ounce (15 kJ/g).[21]

In traditional Chinese medicine, liquorice (मुलेठी, 甘草, شیرین بیان) is commonly used in herbal formulae to "harmonize" the other ingredients in the formula and to carry the formula to the twelve "regular meridians".[37]

Liquorice may be useful in conventional and naturopathic medicine for both mouth ulcers[38] and peptic ulcers.[39]

Its major dose-limiting toxicities are corticosteroid, in nature, due to the inhibitory effect its chief active constituents, glycyrrhizin and enoxolone have oncortisol degradation and include: oedema, hypokalaemia, weight gain or loss and hypertension.[40][41]

Description

It is a herbaceous perennial, growing to 1 m in height, with pinnate leaves about 7–15 cm (3–6 in) long, with 9–17 leaflets. The flowers are 0.8–1.2 cm (⅓–½ in) long, purple to pale whitish blue, produced in a loose inflorescence. The fruit is an oblong pod, 2–3 cm (1 in) long, containing several seeds.[8]The roots are stoloniferous.[9]Chemistry

The scent of liquorice root comes from a complex and variable combination of compounds, of which anethole is the most minor component (0-3% of total volatiles). Much of the sweetness in liquorice comes from glycyrrhizin, which has a sweet taste, 30–50 times the sweetness of sugar. The sweetness is very different from sugar, being less instant and lasting longer.The isoflavene glabrene and the isoflavane glabridin, found in the roots of liquorice, are xenoestrogens.[10][11]

A, phase I metabolites of ILG formed during incubation with rat liver microsomes and NADPH. Based on accurate mass measurements, HPLC retention times, MS/MS analyses, and comparison with data reported by Guo et al. (18), the structures of metabolites M1, M2, M3, M4, M5, M6, and M7 were assigned as liquiritigenin, 7,8,4′-trihydroxychalcone, sulfuretin, 7,3′,4′-trihydroxychalcone, davidigenin, trans-6,4′-dihydroxyaurone, and cis-6,4′-dihydroxyaurone, respectively. B, structures of ILG glucuronide conjugates formed by rat liver microsomes in the presence of UDPGA.

Cultivation and uses

Liquorice grows best in deep valleys, well-drained soils, with full sun, and is harvested in the autumn, two to three years after planting.[8] Countries producing liquorice include Iran, Afghanistan, the People’s Republic of China, Pakistan, Iraq, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Turkey.[12]The world's leading manufacturer of liquorice products is M&F Worldwide, which manufactures more than 70% of the worldwide liquorice flavors sold to end-users.[13]

Tobacco

Most liquorice is used as a flavoring agent for tobacco. For example, M&F Worldwide reported in 2011 that approximately 63% of its liquorice product sales are to the worldwide tobacco industry for use as tobacco flavor enhancing and moistening agents in the manufacture of American blend cigarettes, moist snuff, chewing tobacco and pipe tobacco.[12] American blend cigarettes made up a larger portion of worldwide tobacco consumption in earlier years,[14] and the percentage of liquorice products used by the tobacco industry was higher in the past. M&F Worldwide sold approximately 73% of its liquorice products to the tobacco industry in 2005,[15] and a consultant to M&F Worldwide's predecessor company stated in 1975 that it was believed that well over 90% of the total production of liquorice extract and its derivatives found its way into tobacco products.[16]Liquorice provides tobacco products with a natural sweetness and a distinctive flavor that blends readily with the natural and imitation flavoring components employed in the tobacco industry, represses harshness, and is not detectable as liquorice by the consumer.[16] Tobacco flavorings such as liquorice also make it easier to inhale the smoke by creating bronchodilators, which open up the lungs.[17] Chewing tobacco requires substantially higher levels of liquorice extract as emphasis on the sweet flavor appears highly desirable.[16]

Food and candy

See also: Liquorice (confectionery)

Liquorice flavour is found in a wide variety of liquorice candies or sweets. In most of these candies the taste is reinforced by aniseed oil, and the actual content of liquorice is very low. Liquorice confections are primarily purchased by consumers in the European Union.[12]In the Netherlands, where liquorice candy ("drop") is one of the most popular forms of sweet, only a few of the many forms that are sold contain aniseed, although mixing it with mint, menthol or with laurel is quite popular. Mixing it with ammonium chloride ('salmiak') is also popular. The most popular liquorice, known in the Netherlands as zoute drop (salty liquorice) actually contains very little salt, i.e. sodium;[18] the salty taste is probably due to ammonium chloride, and the blood pressure raising effect is due to glycyrrhizin, see below. Strong, salty candies are popular in Scandinavia.

Pontefract in Yorkshire was the first place where liquorice mixed with sugar began to be used as a sweet in the same way it is in the modern day.[19] Pontefract cakes were originally made there. In County Durham, Yorkshire and Lancashire it is colloquially known as Spanish, supposedly because Spanish monks grew liquorice root at Rievaulx Abbey near Thirsk.[20]

Liquorice is popular in Italy (particularly in the South) and Spain in its natural form. The root of the plant is simply dug up, washed and chewed as a mouth freshener. Throughout Italy unsweetened liquorice is consumed in the form of small black pieces made only from 100% pure liquorice extract; the taste is bitter and intense. In Calabria a popular liqueur is made from pure liquorice extract. Liquorice is also very popular in Syria where it is sold as a drink. Dried liquorice root can be chewed as a sweet. Black liquorice contains approximately 100 calories per ounce (15 kJ/g).[21]

Medicine

See also: Glycyrrhizin

See also: Enoxolone

The compound glycyrrhizin (or glycyrrhizic acid), found in liquorice, has been proposed as being useful for liver protection in tuberculosis therapy, however evidence does not support this use which may in fact be harmful.[22] Glycyrrhizin has also demonstrated antiviral, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective and blood-pressure increasing effects in vitro and in vivo, as is supported by the finding that intravenous glycyrrhizin (as if it is given orally very little of the original drug makes it into circulation) slows the progression of viral and autoimmune hepatitis.[23][24][25][26] Liquorice has also demonstrated promising activity in one clinical trial, when applied topically, against atopic dermatitis.[27] Additionally liquorice has also proven itself effective in treating hyperlipidaemia (a high amount of fats in the blood).[28] Liquorice has also demonstrated efficacy in treating inflammation-induced skin hyperpigmentation.[29][30] Liquorice may also be useful in preventing neurodegenerative disorders and cavities.[31][32][33] Anti-ulcer, laxative, anti-diabetic, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory, antitumour and expectorant properties of liquorice have also been noted.[34][35][36]In traditional Chinese medicine, liquorice (मुलेठी, 甘草, شیرین بیان) is commonly used in herbal formulae to "harmonize" the other ingredients in the formula and to carry the formula to the twelve "regular meridians".[37]

Liquorice may be useful in conventional and naturopathic medicine for both mouth ulcers[38] and peptic ulcers.[39]

References

- "Glycyrrhiza glabra information from NPGS/GRIN". www.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- licorice. Merriam-Webster's Medical Dictionary, © 2007 Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- γλυκύρριζα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- γλυκύς, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ῥίζα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus<

- liquorice, on Oxford Dictionaries

- google books Maud Grieve, Manya Marshall - A modern herbal: the medicinal, culinary, cosmetic and economic properties, cultivation and folk-lore of herbs, grasses, fungi, shrubs, & trees with all their modern scientific uses, Volume 2 Dover Publications, 1982 & Pharmacist's Guide to Medicinal Herbs Arthur M. Presser Smart Publications, 1 Apr 2001 2012-05-19

- Huxley, A., ed. (1992). New RHS Dictionary of Gardening. ISBN 0-333-47494-5

- Brown, D., ed. (1995). "The RHS encyclopedia of herbs and their uses". ISBN 1-4053-0059-0

- Somjen, D.; Katzburg, S.; Vaya, J.; Kaye, A. M.; Hendel, D.; Posner, G. H.; Tamir, S. (2004). "Estrogenic activity of glabridin and glabrene from licorice roots on human osteoblasts and prepubertal rat skeletal tissues". The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 91(4–5): 241–246. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.04.008. PMID 15336701.

- Tamir, S.; Eizenberg, M.; Somjen, D.; Izrael, S.; Vaya, J. (2001). "Estrogen-like activity of glabrene and other constituents isolated from licorice root". The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology78 (3): 291–298. doi:10.1016/S0960-0760(01)00093-0.PMID 11595510.

- M & F Worldwide Corp., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the Year Ended December 31, 2010.

- M & F Worldwide Corp., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the Year Ended December 31, 2001.

- Erik Assadourian, Cigarette Production Drops, Vital Signs 2005, at 70.

- M & F Worldwide Corp., Annual Report on Form 10-K for the Year Ended December 31, 2005.

- Marvin K. Cook, The Use of Licorice and Other Flavoring Material in Tobacco (Apr. 10, 1975).

- Boeken v. Phillip Morris Inc., 127 Cal. App. 4th 1640, 1673, 26 Cal. Rptr. 3d 638, 664 (2005).

- [1] the online Dutch food composition database]

- "Right good food from the Ridings". AboutFood.com. 25 October 2007.

- "Where Liquorice Roots Go Deep". Northern Echo. Retrieved 9 December 2008.

- Licorice Calories

- Liu Q, Garner P, Wang Y, Huang B, Smith H (2008). "Drugs and herbs given to prevent hepatotoxicity of tuberculosis therapy: systematic review of ingredients and evaluation studies". BMC Public Health (Systematic review) 8: 365. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-365. PMC 2576232.PMID 18939987.

- Sato, H; Goto, W; Yamamura, J; Kurokawa, M; Kageyama, S; Takahara, T; Watanabe, A; Shiraki, K (May 1996). "Therapeutic basis of glycyrrhizin on chronic hepatitis B.". Antiviral Research 30 (2-3): 171–7.doi:10.1016/0166-3542(96)00942-4. PMID 8783808.

- van Rossum, TG; Vulto, AG; de Man, RA; Brouwer, JT; Schalm, SW (March 1998). "Review article: glycyrrhizin as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C." (PDF). Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics12 (3): 199–205. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00309.x.PMID 9570253.

- Chien, CF; Wu, YT; Tsai, TH (January 2011). "Biological analysis of herbal medicines used for the treatment of liver diseases.". Biomedical Chromatography 25 (1-2): 21–38. doi:10.1002/bmc.1568.PMID 21204110.

- Yasui, S; Fujiwara, K; Tawada, A; Fukuda, Y; Nakano, M; Yokosuka, O (December 2011). "Efficacy of intravenous glycyrrhizin in the early stage of acute onset autoimmune hepatitis.". Digestive Diseases and Sciences56 (12): 3638–47. doi:10.1007/s10620-011-1789-5.PMID 21681505.

- Reuter, J; Merfort, I; Schempp, CM (2010). "Botanicals in dermatology: an evidence-based review.". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology11 (4): 247–67. doi:10.2165/11533220-000000000-00000.PMID 20509719.

- Hasani-Ranjbar, S; Nayebi, N; Moradi, L; Mehri, A; Larijani, B; Abdollahi, M (2010). "The efficacy and safety of herbal medicines used in the treatment of hyperlipidemia; a systematic review.". Current pharmaceutical design 16 (26): 2935–47. PMID 20858178.

- Callender, VD; St Surin-Lord, S; Davis, EC; Maclin, M (April 2011). "Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation: etiologic and therapeutic considerations.". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 12 (2): 87–99. doi:10.2165/11536930-000000000-00000. PMID 21348540.

- Leyden, JJ; Shergill, B; Micali, G; Downie, J; Wallo, W (October 2011). "Natural options for the management of hyperpigmentation.". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 25 (10): 1140–5. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04130.x. PMID 21623927.

- Kannappan, R; Gupta, SC; Kim, JH; Reuter, S; Aggarwal, BB (October 2011). "Neuroprotection by spice-derived nutraceuticals: you are what you eat!" (PDF). Molecular Neurobiology 44 (2): 142–59.doi:10.1007/s12035-011-8168-2. PMC 3183139.PMID 21360003.

- Gazzani, G; Daglia, M; Papetti, A (April 2012). "Food components with anticaries activity.". Current Opinion in Biotechnology 23 (2): 153–9.doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2011.09.003. PMID 22030309.

- Messier, C; Epifano, F; Genovese, S; Grenier, D (January 2012). "Licorice and its potential beneficial effects in common oro-dental diseases.". Oral Diseases 18 (1): 32–9. doi:10.1111/j.1601-0825.2011.01842.x. PMID 21851508.

- Shibata, S (October 2000). "A drug over the millennia: pharmacognosy, chemistry, and pharmacology of licorice.". Yakugaku Zasshi 120 (10): 849–62. PMID 11082698.

- Fiore, C; Eisenhut, M; Ragazzi, E; Zanchin, G; Armanini, D (July 2005). "A history of the therapeutic use of liquorice in Europe.". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 99 (3): 317–24. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2005.04.015.PMID 15978760.

- Ming, LJ; Yin, AC (March 2013). "Therapeutic effects of glycyrrhizic acid.". Natural Product Communications 8 (3): 415–8.PMID 23678825.

- Bensky, Dan; et al. (2004). Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition. Eastland Press. ISBN 0-939616-42-4.

- Das, S. K.; Das, V.; Gulati, A. K.; Singh, V. P. (1989). "Deglycyrrhizinated liquorice in aphthous ulcers". The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 37 (10): 647. PMID 2632514.

- Krausse, R.; Bielenberg, J.; Blaschek, W.; Ullmann, U. (2004). "In vitro anti-Helicobacter pylori activity of Extractum liquiritiae, glycyrrhizin and its metabolites". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 54 (1): 243–246.doi:10.1093/jac/dkh287. PMID 15190039.

- Olukoga, A; Donaldson, D (June 2000). "Liquorice and its health implications.". The Journal of the Royal Society for the Promotion of Health 120 (2): 83–9. doi:10.1177/146642400012000203.PMID 10944880.

- Armanini, D; Fiore, C; Mattarello, MJ; Bielenberg, J; Palermo, M (September 2002). "History of the endocrine effects of licorice.".Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & diabetes 110 (6): 257–61.doi:10.1055/s-2002-34587. PMID 12373628.

National Institute of Health - Medline- PDRhealth.com - Profile of Deglycyrrhizinated Licorice (DGL)

- Chemical & Engineering News article on Licorice

- Non-profit site on the health aspects of licorice/liquorice

- Medical use of irritation on chest

Synthesis, anti-tubulin and antiproliferative

structure–activity relationship of steroidomimetic dihydroisoquinolinones

Synthesis, anti-tubulin and antiproliferative

structure–activity relationship of steroidomimetic dihydroisoquinolinones Nanoparticles responsive to reactive oxygen species and low pH

deliver therapeutics directly to sites of inflammation

Nanoparticles responsive to reactive oxygen species and low pH

deliver therapeutics directly to sites of inflammation